Cree entrepreneur Mallory Yawnghwe stands in front of a map of Canada. It’s filled with Indigenous place names—and their meanings—from coast to coast to coast.

“There’s amiskwaciy-wâskahikan,” she says, pointing to what is also known as Beaver Hills House or Edmonton. “This was the hub of trade and commerce for so many nations.”

Cree, Blackfoot and Nakoda were some of the First Nations who used to gather along the North Saskatchewan River to trade goods before the arrival of European explorers.

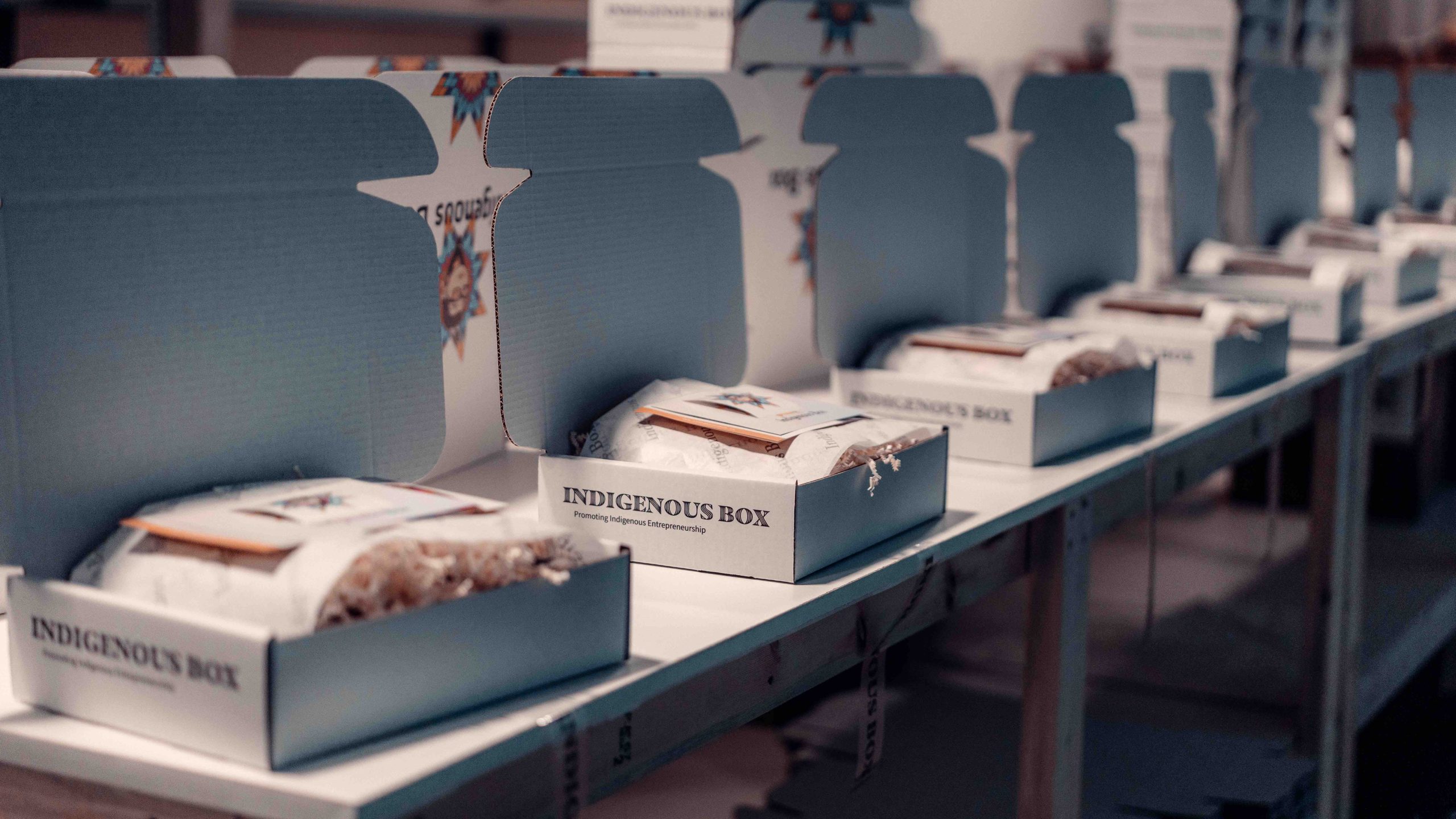

The map hangs on one of the bright blue walls of Indigenous Box, an online business founded by Yawnghwe and her husband, Kham, in 2021. In 12 months, they’ve grown their company from a $5,000 start-up grant to $1.3 million in sales, she says.