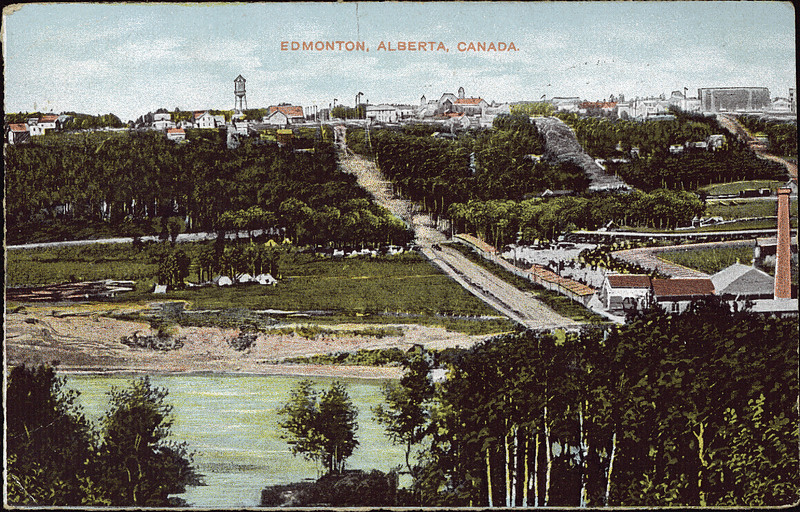

Palahna Kosovan didn’t want to move to Edmonton.

Or anywhere in Canada, for that matter.

The year was 1914. She was living with her family in a town in Galacia—what is now part of Ukraine—and wanted to stay there. Her father wanted her to marry Nikolai Maksymiuk, who had immigrated to Edmonton years earlier.

“No, I don’t want to go,” Pahlana recounts in a 1975 documentary, Great Grand Mother.

“Because I don’t know Canada, because I’m scared. I know it’s 23 years I live over there [in Galacia], maybe it’s danger for me, it’s one boy, only one time I see him. It’s not handy for me to go but I have to go.”