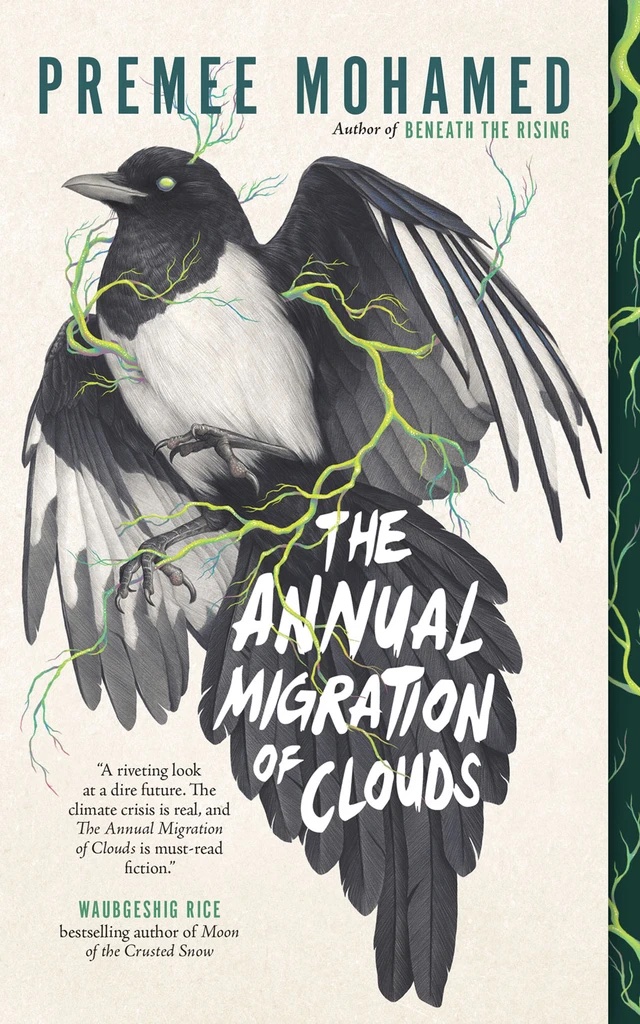

In Premee Mohamed’s 2021 novella, The Annual Migration of Clouds, a young girl and her mom struggle to stay alive in a world ravaged by climate change.

Both suffer from a sinister new disease, a fungal parasite which seems to control their thoughts and movements. The two live and work in what used to be the University of Alberta’s Biological Sciences Building, one of the few “sturdy” structures that can sustain life. Wild boars roam the river valley, largely devoid of trees due to a series of storms, landslides, wildfires and melting glaciers. Children play amongst the “crumbling ruins” of the Legislature.

Edmonton is a frequent backdrop in Mohamed’s science fiction, which often deals with calamities—whether caused by ancient monsters or climate disasters.

“I don’t think it’s realistic to write anything set in the future on Earth and NOT mention climate change,” says the Clareview resident.