Rollie Pemberton is one of Edmonton’s most celebrated artists and performers.

You might know him better as Cadence Weapon, the rapper behind such tracks as SENNA, Hope in Dirt City, and his ode to a certain Oilers superstar, Connor McDavid. Pemberton’s record, Parallel World, won the Polaris Music Prize (and $50,000) for best Canadian album in 2021.

“I want to show everybody, all the young artists listening right now, and watching this, you don’t have to be from Toronto,” he said during his acceptance speech.

“Your experience is valuable. Your art matters. Coming from Edmonton, I don’t want you to forget that. The prairies got something to say. E-town.”

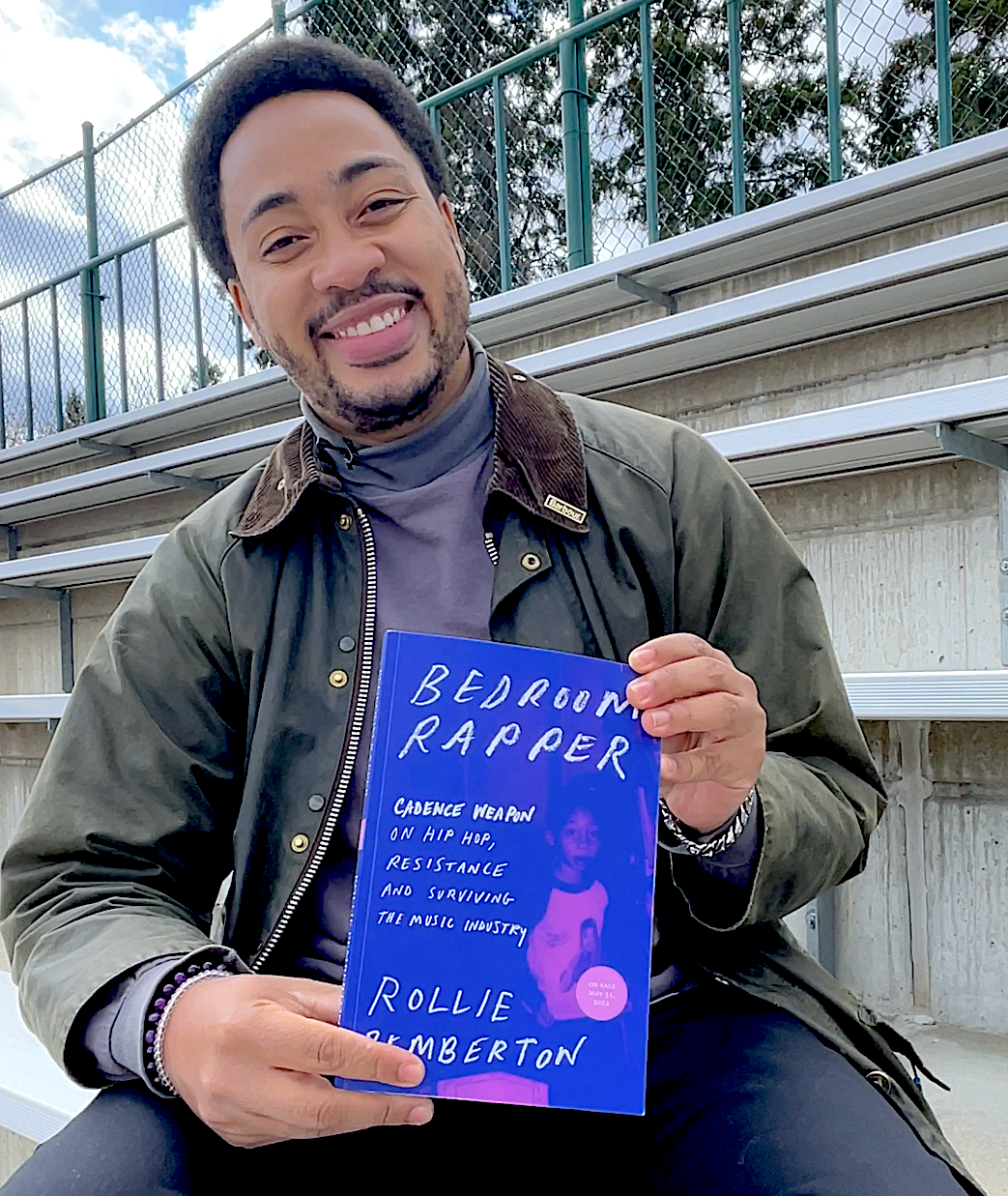

Pemberton writes about his hometown in his first memoir, Bedroom Rapper: Cadence Weapon on Hip Hop, Resistance and Surviving the Music Industry, now available through McClelland & Stewart.

He documents his early days as a rapper, poet and music critic in E-town—from writing rhymes in math class at St. Francis Xavier High School to the release of his first album, Breaking Kayfabe, to his time as Poet Laureate for the City of Edmonton from 2009 to 2011.

“In Edmonton, the winters are long, which gives you plenty of time to stay inside and create,” Pemberton writes.

Bedroom Rapper also covers his eventual move to Montreal (and then Toronto), his struggles with his record label and the industry in general, and his triumphant Polaris win.

Pemberton recently discussed his hometown and memoir.

Q: How did the city’s music scene shape you?

Rollie: I really resonated with electronic bands like Shout Out Out Out Out and DVAS, anybody with a synth. I really felt like “OK, this is a scene I can kind of belong in.” I didn’t really get as much support from the rap scene here, you know? I didn’t sound like anybody else, I didn’t look like anybody else. It was lonely, but I think it really drove me to be who I am today, which is why I have this insane drive and self belief. I’ve just fought the whole time.

Q: You were Edmonton’s Poet Laureate for two years. What impact did it have on your career?

Rollie: It had a major impact. It forced me to get more serious with my lyricism. At the time, I was having fun, I was making music for my friends, with inside jokes and things. When I became the Poet Laureate, I saw a higher level of scrutiny, where people were really putting everything I said under a microscope and taking things out of context. You know, taking a party rap tune and comparing it to Shakespeare—doing things with coded racism. It’s aggravating, annoying, but it just really made me step my game up. Everything I wrote after that has the same depth of any poetry.

Q: What was it like to write your memoir?

Rollie: I’d go to the studio and work on [Parallel World] by night, and I’d wake up early in the morning and write the book. The thing about the book that was cool was it was different every day. One day, I’d be really shredding and write 2,000 words a day and then the next day, I wouldn’t write anything and it would be scary. I was like, “Oh, no, I can’t really control this.” But then I would do other things—I would organize ideas, do research or go through my emails.

That was a big part of the process—going through emails from 2005, corroborating what happened. If you ever have the chance, you should try and look at an email you wrote 20 years ago. It’s really painful. I used to write all lowercase like I was bell hooks.

Q: Your memoir covers a lot of ground, including Edmonton’s music scene in the early 2000s and the history of hip hop. How important was it for you to write about these topics?

Rollie: There’s no me without my community. It’s kind of like, “This is our story.” It’s not just about me. I couldn’t have been me without the people around me. I have a whole chapter about the Edmonton music scene. It’s like a perfect storm of the people who are involved and how we react to each other and react to what we all are creating.

There’s something I mentioned in the first chapter—growing up in Edmonton, every time I’d say I was a rapper, I had to explain the history of rap to every person. And now I’m doing it in the book. I want it to be a resource, something that people find useful. I didn’t want to just do a book that’s like: “Yo, I did this.”

Q: How do you think Edmonton has shaped you?

Rollie: I think it gives me that kind of underdog mentality. Edmontonians, we feel underappreciated, we feel kind of forgotten.

Read about life in Edmonton—stories of business, innovation and the people who make it happen.

Read about life in Edmonton—stories of business, innovation and the people who make it happen.

Read about life in Edmonton—stories of business, innovation and the people who make it happen.